LEN JOHNSONBorn in Manchester in 1902, Len Johnson learned the noble art on the boxing booths of Bert Hughes and ‘Professor’ Bill Moore, and eventually became the owner of his own booth – travelling the roads and towns of England with fairgrounds.

Johnson developed into a highly skilled boxer, with an educated left hand and a slippery defence that made him difficult to hit and left his features largely unmarked throughout his career.

Managed by his father, Bill, Len embarked on a conventional boxing career in 1921 that saw him win more often than he lost, but seemed to be headed nowhere in particular.

Len Johnson’s boxing career took a dramatic turn in early 1925 when he was matched with Roland Todd, the reigning British and former European middleweight champion, in a non-title fight.

The result was a conclusive 20 rounds points verdict for Johnson, and this had a considerable effect on re-aligning the Manchester man’s aspirations. From this point onwards, Johnson steadily began to dominate the British middleweight division, with wins over Roland Todd in a rematch, former World Welterweight Champion Ted ‘Kid’ Lewis (stopped in nine rounds), Len Harvey, Gipsy Daniels, George West, Ted Moore, Jack Etienne, Harry Crossley, Leon Jaccovacci, Michele Bonaglia, plus many other leading British and European middle and light heavyweights of the period.

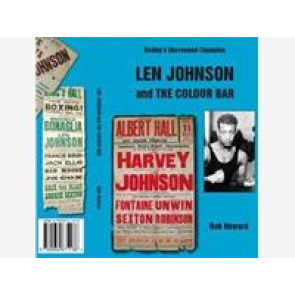

Unfortunately for Johnson, British boxing operated a rule known as the ‘colour bar’ in the 1920s (repealed in 1948) that prevented anynon-white boxers from fighting for championships. Johnson lobbied newspapers and politicians over a period of several years, only to meet with an unchanging negative response and indifference to his situation.

Johnson spent the first half of 1926 in Australia, where he won the British Empire middleweight championship by defeating local hero Harry Collins. Johnson was popular and very successful in his six months Down Under, returning home to get married.

On arrival in England, Johnson discovered that his Empire title – won fair and square against a formidable opponent – was not recognised by the National Sporting Club, who controlled British boxing at that time. In fact, the NSC had installed Scotland’s Tommy Milligan as British Empire Champion – openly snubbing the man now generally regarded by boxing fans everywhere as Britain’s best middleweight, albeit unofficially.

Johnson’s Empire title victory, and two successful defences – all in Australia – only entered the boxing record books many years later, due to the intransigence of officialdom.

In 1930 Johnson visited America on three occasions looking for fights, on trips organised by New York promoter Jimmy Johnston, but proposed contests did not materialise. In the same year, Johnson became the proprietor of his own booth – realising a long-held ambition. From this point onwards, however, eyesight problems and the onset of rheumatism caused a steady decline in Johnson’s ring performances. In 1932 he lost a rematch with Len Harvey in a contest that promoter Jeff Dickson billed as being for the British middleweight championship, in defiance of the British Boxing Board of Control. The BBB of C (formed in 1929) had taken over control of British professional boxing from the NSC, but had retained the colour bar in its constitution.

Later the same year, 1932, Johnson travelled to Paris where he was forced to retire after eight rounds against the rugged Marcel Thil, then fighting at peak form. By the end of 1933, Johnson had retired from boxing, concentrating thereafter on running his travelling booth.

Shortly after war broke out in September 1939, Len Johnson sold his boxing booth and dedicated the next few years to the war effort by joining the Civil Defence. This marked the end of Johnson’s active involvement in boxing, although he did, in the 1950s, write a boxing column for the Communist Party newspaper, The Daily Worker. After the war, he joined the Communist Party and also became active in trade union matters, causing himself to become a thorn in the side of officialdom. Although Johnson failed six times to become elected to Manchester City Council, he acted for many years as an unofficial representative of the city’s black community – personally intervening in disputes involving racism. Len Johnson is remembered by many today as a figure who spent a lifetime in a personal battle against injustice and racism.

Keep me informed of updates